Looking at Labor and the Labor of Looking

Residency Unlimited, "Clocking In, Clocking Out," on view through July 2.

No matter the culture or era, humans have always craved increasingly efficient and convenient access to food prepared by others. This practice has roots stretching back to ancient civilizations, but the modern meal delivery service as we know it traces its origins to 1890, when Mahadeo Havaji Bachche established the very first organized meal delivery system in India. With about a hundred men, he launched a service that brought home-cooked food to people at their workplaces. Each delivery man was called a “dabbawala,” which translates to “one who carries a box.”

Fast forward to present-day New York City: it’s nearly impossible to travel through any borough without passing delivery drivers zipping by on e-bikes, carting fresh meals and miscellany delights to our doorsteps. As of 2024, over 65,000 app-based food delivery workers navigate the city daily, collectively powering an industry that generates billions of dollars each year. For many New Yorkers, delivery apps have become an everyday convenience — but for the workers themselves, the conditions are far more precarious.

In response to mounting concerns over low pay, unsafe conditions, and exploitative algorithms, New York City1 passed landmark legislation in 2023 to set a minimum wage for app-based delivery workers. The law guarantees a base pay rate of at least $17.96 per hour (before tips), with planned increases to match inflation in coming years. Meanwhile, crackdowns on illegal e-bike seizures and new safety regulations continue to reshape the landscape in which these workers operate.

For artist fields harrington, these couriers and their bikes have become the focal point of a new series of photographs featured in Jesse Firestone’s timely exhibition Clocking In, Clocking Out, on view as part of Residency Unlimited’s 2025 NYC-Based Artist-in-Residence culminating exhibition. According to the press release, Clocking In / Clocking Out “emerges from within this loop of labor and time, considering how time and work structure the conditions of visibility, agency, and endurance.” The show spans multiple mediums, but what struck me most in harrington’s work is his daring attempt to test the boundaries of what photography can do.

Photography has long been understood as an extractive practice — deeply entwined with larger questions of representation, documentation, autonomy, and, of course, commerce. After a recent studio visit with harrington (thank you, Jesse!), I’m still suspended in the tension of his ways of seeing. I admit, at first I was skeptical. Like many, I carry a healthy suspicion toward the ethics of documenting, narrating, and commodifying the lives of others. What does it mean to photograph people at work? How do we responsibly tell stories that can — and perhaps should — be told in other ways? What role do the author and the audience play in the interior lives of any subject?

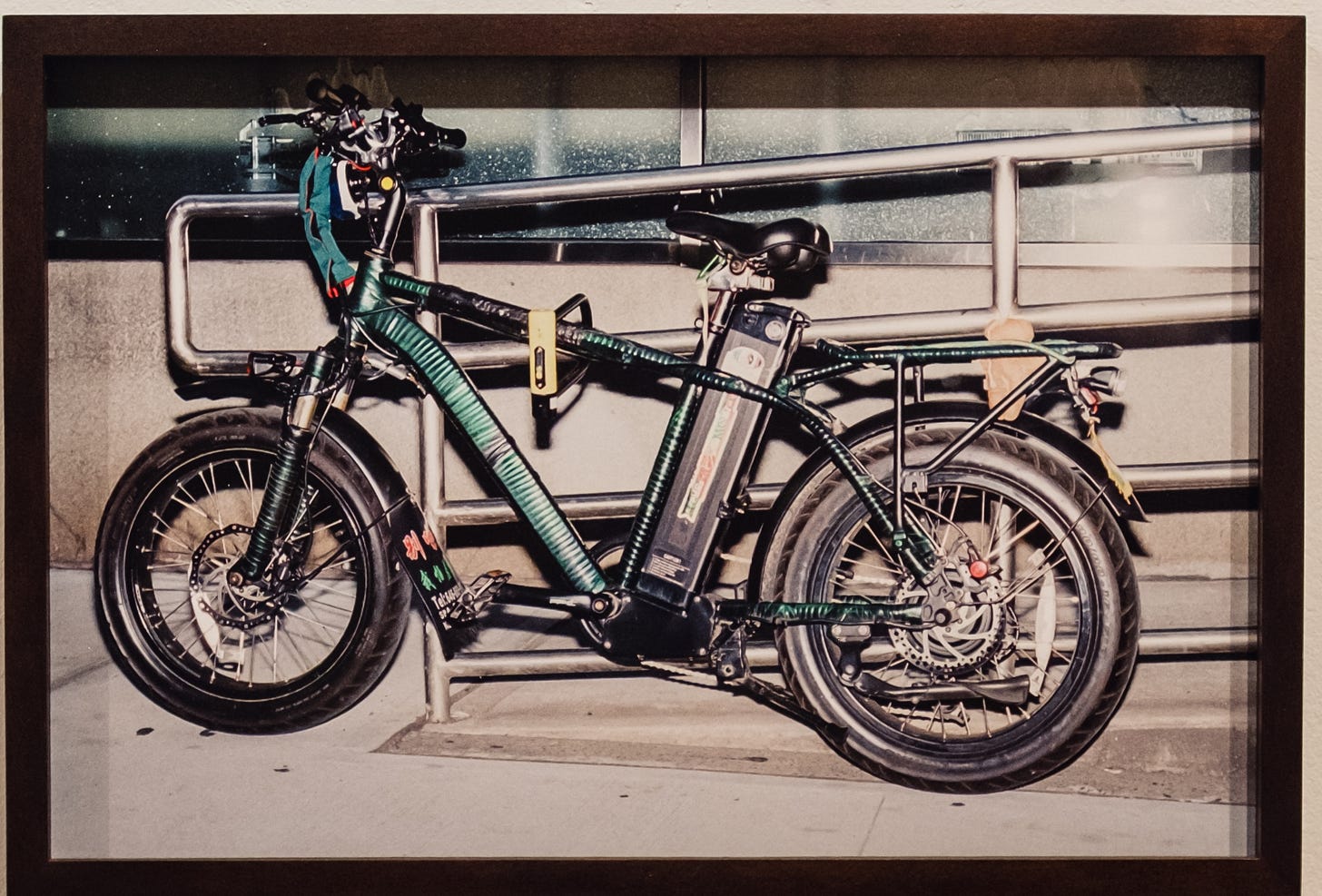

Through what feels like a kind of self-flagellation, harrington continues to position his lens at this labyrinthine crossroads. After shadowing several, often (and justifiably) hesitant drivers, he chose to pause documenting the workers themselves and turned his focus toward the bikes. He grew curious about the bikes and their construction — for example, exploring the link between the batteries that power the bikes and the countries of origin of the riders using them. What does it mean for a driver to seek refuge from the very country whose mineral resources power the labor they now do thousands of miles away?

In documenting thousands of bikes, certain patterns began to emerge: symbols of home, religious imagery (think prayer hands and images of the Virgin de Guadalupe), and subtle signs of personalization that many (myself included) might never have stopped to notice. During our visit, it was amazing to hear the artist think through how to tackle questions of labor from a truly holistic perspective. What has resulted — at least for now — is an assembly of photographs: still-life images that reveal a striking diversity among these vehicles and, by extension, their riders. Is it a perfect solution? Perhaps not. But have these images fundamentally changed how I see these bikes — and the strategies for survival they facilitate? Absolutely.

One of my favorite things about artistic practice is that artists — unlike most other public thinkers — can exist within the space of hypothesis. Art and culture are critical allies to policy, but on their own, they remain spaces of curiosity and experimentation. I’ll let fields keep his secrets about future iterations of the project, but what exists today — shown alongside equally compelling work by artists including Ayanna Dozier, Cato Ouyang, and Bat-Ami Rivlin — is the beginning of something I have no doubt is worth continuing to resolve. Clocking In, Clocking Out represents a collection of ritualistic, process-based artworks that grant so much more than the eye can see, and for that I’m deeply thankful.

Clocking In / Clocking Out

Residency Unlimited’s 2025 NYC-Based Artist-in-Residence (NYCBAR) Exhibition

Featuring Ayanna Dozier, Cato Ouyang, fields harrington, and Bat-Ami Rivlin

Curated by Jesse Bandler Firestone

All Street Gallery, June 12 – July 2, 2025

Legislation passed in 2013 was due to the incredible organizing efforts of groups including but not limited to The Workers’ Justice Project, Los Deliveristas Unidos, and Desis Rising Up & Moving.

fields harrington's practice is in conversation with Allan Weber's exhibition "My Order" at Nottingham Contemporary. Weber (b. 1992, Brazil) documented his experience in food delivery during Covid in the favelas of Rio de Janerio and Nottingham. It is hopeful to see a larger dialogue that is reflective and critical of the realities of labor for the working class post-Covid.